By: Mariah Alanskas

The first time I experienced grief was in a funeral home bathroom. I hadn’t really known my great-grandmother other than her calling me Margaret, likening me to her sister because of Alzheimer’s disease wreaking havoc on her brain.

Yet, I couldn’t help but feel the heavy weight of loss from those around me. I was twelve, wearing a black dress I adamantly fought my mom over, sitting in a small, poorly decorated bathroom and crying over a woman I only got to know through short glimpses when her memory aligned— and when she remembered my real name.

At the time, I don’t think I was actually grieving. I was just feeling.

Throughout the years following my great-grandmother’s death, I saw grief many times in many different forms. During the lineup of condolences dished out at wakes, I saw collections of strained smiles, steady handshakes and pointedly ignored eye contact, as well as those avoiding the interactions altogether, attached to the back of the room, like picture frames on a wall.

Yet, I still hadn’t really known grief.

So when my grandmother passed away from kidney complications in 2020, I truly had no idea how to react. I wasn’t in denial, but I couldn’t cry either…. at least not at first. I just felt….. uncomfortable. And I couldn’t help but think “what was I supposed to be feeling?”

In 1969, the five stages of grief as we know them were outlined by a Swiss-American psychiatrist by the name Elisabeth Kúbler Ross, in her book “On Death and Dying.”

Although at the time Ross based these stages on what people can feel after being diagnosed with a terminal illness, we have adopted them today as an all encompassing determination for the emotions and feelings we carry over death, disappointment and beyond.

But grief is a funny thing. It is fickle, cruel and generally unyielding.

A few weeks after my grandma’s death at a rather small, early COVID days-esque funeral, I again, found myself crying in the bathroom of a funeral home in a black dress. Only this time, I had not fought my mother on wearing it.

Grief would hit both me and my mother in odd ways in the wake of her death, none of which seemed to be in the ways I thought it should— through the stages of grief.

I wondered if things would ever go back to the way they were before her death, when life would become “normal” again and if the endless stream of tears would ever stop filling up the ocean that had consumed our lives.

Though apparently according to Tim Larson, a counselor trainee at Kelly’s Grief Center located in Kent, Ohio, this was our “new normal.”

I wanted to know if grief ever “ends,” if there is truly a way to explain it or if it was something we have to learn to live with.

Larson himself has an intimate relationship with grief, as he decided to become a counselor following the death of his brother.

“I found that during that time, people just really need someone to be there with them, and not everyone has that,” Larson says. “So, I felt like I could go into this profession and try to be that for some people during that time. That I’d feel like I’m making a positive impact on the world.”

Larson says Dr. Ross herself explained the stages aren’t “linear.” That you don’t accomplish one stage and think “you’re done.” You also may not go through all the stages one time—or all of them at all.

But are five stages still enough?

I didn’t think so as I watched my mother’s spontaneous tears drop down her face while washing dishes. While I hugged her in comfort and then cried while taking a shower afterwards.

It’s called a “process,” but in reality— I think grief becomes a state of being. It has been nearly four years since my mother’s mother’s death, and although I don’t feel me or my mother thinking about her anymore on a near-daily basis, I still see and feel “it” hit at random moments…. especially in my mom.

Grief has stuck to her like a thick syrup on a linoleum table. It hits her in the most untimely ways in places like grocery stores and restaurants. And yet, all of her visceral reactions have never seemed to fit so simply into a singular “stage.” Rather, they morph into a collection of them, or like she has created her own version of a new emotion we have yet to find the words for.

Even nearly four years to the date of my grandmother’s death, she can still be found frequenting my grandmother’s grave, planting and placing fresh flowers for each season, holiday and the random days she finds herself engulfed in grief.

“I don’t even know if your uncles go there anymore,” my mother told me, “And your grandfather goes there sometimes.”

I asked her how often she makes the two mile trek to the grave on the hill from my childhood home to replace the flowers.

“I do it all the time,” she said. “I replace them because I don’t want them lying there dead.”

On one side I see the beauty in this ritual she has created, constantly ensuring that life is blooming around my grandma’s headstone. But, on the other hand I see it as something that could be holding her back from healing— the idea that she feels like the only one who is committed to ensuring the beauty surrounding the final resting place of my grandma’s ashes.

Considering other solutions

In terms of “healing methods,” Larson says everyone mourns differently in terms of what they are mourning— whether it’s the person themselves, the loss of their role to that person (such as a daughter, caregiver, ect.) or a mix of the two.

“There’s a couple schools of thought that are different at this point,” according to Larson. “There’s one that talks about the tasks of mourning, and there’s one that talks about the phases of grief. Both are kind of interchangeable, they’re very similar to Kubler Ross’s initial five stages, but I kind of liked the idea of the tasks of mourning because it gives you the idea that these are things to accomplish, but tasks are never fully complete.”

J. William Worden is an American psychologist’s whose “tasks of mourning” include:

“It’s similar to Kubler Ross’s stages about acceptance, but it’s finding a way to move forward with your life while honoring the one that you lost,” Larson explains. “Because you’re still integrating the person that you love that is no longer with you into your life—- it’s about just having them in your life in a different way.”

Although I had never personally heard of the “tasks of mourning,” before speaking with Larson, there are two things in particular I like about them. Well, maybe three things.

One, they were coined a little more recently than the stages were and have been adapted up until recently, with the last published tweaks being in 2018.

And two, that they are set up as “tasks” and not “steps.”

Though inadvertently, Ross’s steps have always come across as a 1,2,3,4,5 step process, rather than a continual cycle, as she has suggested previously.

I also like that the tasks seem almost ambiguous.

The idea of the third task, “processing the pain of grief,” is more broad and objective than the curt five single words of the defined stages. It is not to say that the stages are entirely inaccurate though either. Rather, they are just too simple.

I do feel like I watched my mother go through most of the five phases, but I feel even more that I saw her go through the “tasks,” though I’m not sure she ever got to truly check them off her list.

I think she is stuck in that third task, like a continual loop.

It is in that loop I see the guilt my mother carries for not being closer to her mother while she was still alive. The confusion she still struggles with about who she is as a person, and the anger she feels for how her life has irrevocably changed.

“We weren’t close when I was growing up,” she said. “I’ll always regret that. There’s so much I wish I could have said.”

I’ve learned her grief is complex, as she isn’t just mourning her mother, she’s also grieving the loss of ever getting the chance to better their relationship.

As someone who saw the “toughness” in my grandma, but saw more of the gentle touch she gained in her later years, I feel the grief in much simpler ways.

I feel it in the ways that I know I’ll never have a woman so prominent in my life at my wedding, like she was for my much older brother. Looking back at me in a long, formal gown the way she once did when she saw me before a high school dance. The way she will never again randomly tell me how proud she is and how I will never ever see her fierce protective nature surface whenever she rediscovers that yes, her grandchildren do occasionally leave the safe confines of home.

It is unavoidable that me and my mother will feel these feelings in a myriad of ways throughout the rest of our lives– both connected by a fine line of matriarchal bond.

But what it doesn’t mean is that history needs to repeat itself. I think it is both me and my own mom’s hope that if I one day too have to mourn my mother, I can do so in a way without regret.

Although she doesn’t know it, I found a journal my mother started to leave for me in the case of her passing.

I didn’t read it, but I can guess what it would contain inside— notes about her own relationship with her mother and how she felt like “she never truly knew her.”

“There’s a man named Dr. Wolfert,” Larson explains. “Who says that grieving is often like wandering through the wilderness, and there’s no set path to find your way through the wilderness.”

Moving On

In my mother’s case, it feels like she is mainly through the “wilderness,” though she seems to take a wrong turn or two every once in a while.

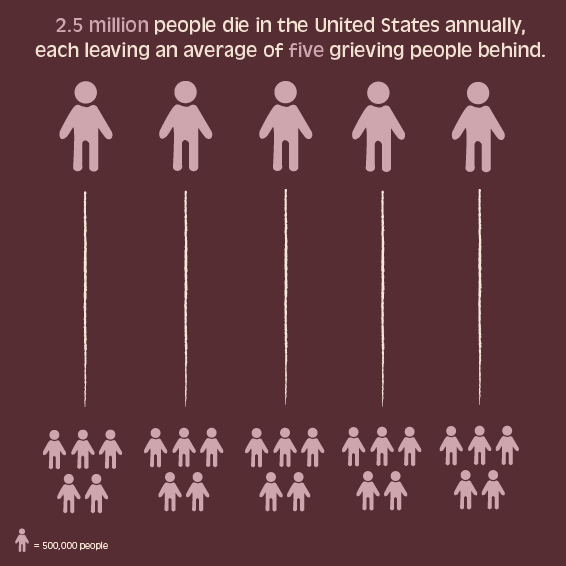

According to the Recovery Village, About 2.5 million people die in the United States annually, each leaving an average of five grieving people behind.

That is a lot of people. And by watching and feeling the grief that was left in the wake of my grandmother’s death— an ever larger magnitude of grief I can barely fathom.

“On a societal level, we [need to] just understand that how people grieve is how they grieve,” Larson says. “You know somebody may grieve by doing tasks or activities instead of openly weeping and things like that.” That’s okay, we don’t need to tell them whether they’re doing it wrong or right…. We just need to meet people where they’re at.”

Larson says grief counseling is not for everyone. It most definitely wasn’t for my mother.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” she said. “It feels like being stabbed with a knife.”

What I’ve learned about grief is that while you may find ways to accept your grief and move on with your life, it is always an ongoing process. Our only true hope is to use the grief that we feel in ourselves and see in others to find clarity, learn from regrets and to keep pushing forward.

And so, I’ve tried to do what Larson suggested. I’ve tried to meet my mother where she is at. Instead of trying to decipher which “stage” or phase of grief she is in, I’ve just simply been there. Laughing over inside jokes, telling her about my day and asking her about hers like how a normal twenty something-year-old would talk about with her mom, each of us working to ensure we truly know each other— that is until her next wave of grief hits, pulling her under like an unyielding ocean wave.

Leave a comment